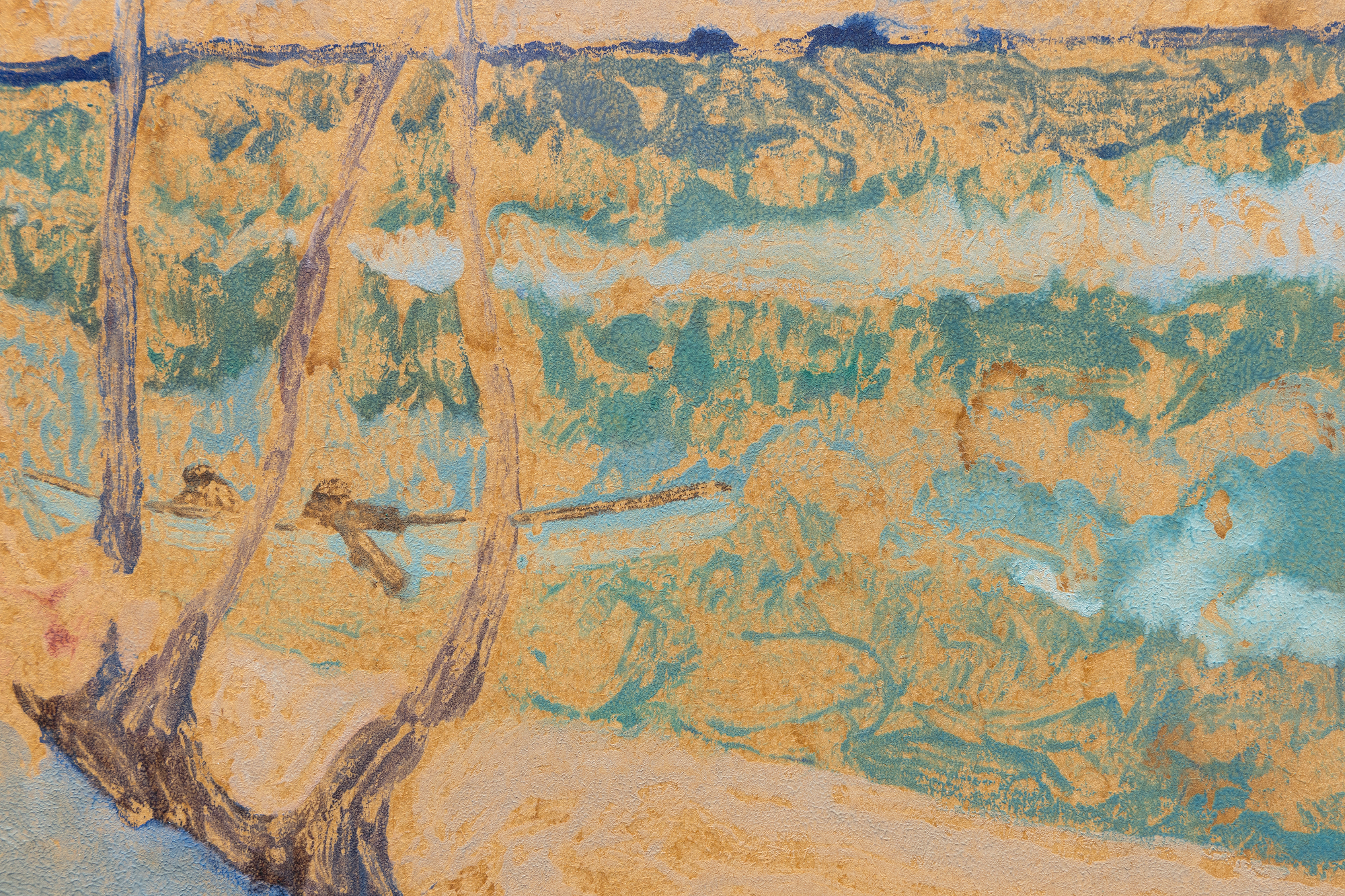

PAUL GAUGUIN (1848-1903)

Provenance

Private collection, LondonChristie's London, September 16, 2015, lot 18

Private collection, acquired from above

Literature

Richard S. Field, Paul Gauguin: Monotypes, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, 1973 (not recorded; see no. 99 for a related work)Richard Brettell, The Art of Paul Gauguin, National Gallery of Art, Washington/ Art Institute of Chicago, 1988, pp. 480-487 (not included; see nos. 272 & 273 for related works)

Ruth Pielkovo (transl.), The Letters of Paul Gauguin to Georges Daniel de Monfreid, New York, 1922, p. ...More...161

...LESS...

150,000

“Bathers” belongs to Gauguin's 1899–1903 series of "traced monotypes," a technique where the artist drew or pressed on the back of paper placed over an inked or painted surface, resulting in a single reversed impression. This process introduced subtle textures and a sense of immediacy while allowing Gauguin to explore the interplay of positive and negative forms. By late 1902, the artist had begun keying the drawings on the versos of these monotypes to the direction of his paintings, resulting in a deliberate reversal of themes. The reversed orientation of this monotype, for example, is associated with the painting "Famille tahitienne" (W.618, Stephen A. Cohen collection, a.k.a., “A Walk by the Sea”), and it exemplifies this practice, raising intriguing questions about the creation sequence.

The reversed orientation offers a compelling argument for understanding the monotype as a concurrent experiment rather than a preparatory study. Rather than serving as a preliminary blueprint, the monotype served as a dynamic tool for experimentation, allowing Gauguin to analyze and retest compositional ideas, color harmonies, and spatial relationships in real-time. The act of transferring the image introduced an element of unpredictability—textures softened, colors became more fluid, and linear forms took on painterly qualities. This spontaneity enabled Gauguin to step outside the constraints of oil painting, offering him fresh insights into how elements of the composition could evolve. Through this iterative process, the monotype would have informed adjustments to “Famille tahitienne,” enriching the painting's vibrancy, depth, and compositional balance. The interplay between the two mediums underscores Gauguin's innovative approach, treating the monotype not as a secondary exercise but as an integral part of his artistic vision.

While the monotype lacks the polished refinement of the painting, its raw immediacy and formal sensitivity reveal Gauguin's fascination with experimentation and spontaneity. Far from being a preparatory study, “Bathers” likely enabled Gauguin to deconstruct and reimagine “Famille tahitienne” as he worked. This creative interplay underscores Gauguin's broader artistic quest during his later years: to distill the essence of life and nature into forms that combine immediacy with timeless resonance.