Please contact the gallery for more information.

Current Exhibitions

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2016

2015

2014

2011

2010

2009

Images: Copyright ©Pacific SunTrading Company, Courtesy Frank E. Fowler and Warren Adelson

History

As one of the most celebrated and successful artists of all time, Andrew Wyeth exhibited transparent watercolors to great acclaim and by the 1940s had mastered the precisely descriptive drybrush and tempera styles. Together, the three distinct mediums brought acclaim that eclipsed that of his father Newell Convers Wyeth, perhaps the greatest American illustrator of its golden age. When, in 1948, Andrew painted Christina’s World, he and Jackson Pollock were fiercely independent artists who peacefully coexisted at opposite poles of art in America. But that was all to change. Two decade later, Wyeth, the artist a New York University art professor called, “the last authentic survivor of a very endangered 19th century species” became an institutional pariah at the expense of art critics who reslotted him as an old-fashioned artist living in a different century. Wanda Corn, wrote the exhibition catalogue for his first west coast show at the De Young Museum in 1973. She wondered why he did not suffer at their expense. “But he didn’t really. He never stopped making pictures. He used to say, ‘I only know one thing to do. I only know how to make art.”

When Andrew Wyeth hinted he had a cache of secret drawings and paintings he did not wish to be seen, the words ‘secret’ and ‘hidden’ were interpreted as ‘discovery’ and ‘treasure’ by the lead on the story, Art and Antiques editor Jeffrey Schaire. He was granted the scoop, the story broke a year later in August 1986, and Andrew Wyeth’s fifteen year obsession with a mysterious woman named Helga spilled beyond the art world and became an international news phenomenon. Picasso never graced the covers of both Time and Newsweek the same week, but Andrew Wyeth did. Other news followed: a collector, or, rather an investor, Leonard B. Andrews purchased the collection in its entirety, The National Gallery came calling with the promise of an exhibition of over half of the 240 drawings, drywash and tempera works and most astonishingly, millions of impressions of the tempera, Braids, all printed within two weeks during the summer of 1986 were hastily readied to be circulated making it along with Warhol’s soup cans, one of the most recognizable images in the world.

Wyeth stated he was drawn to “Helga because of her German qualities: her strong, determined stride, the green Loden coat she often wore, and the long braids of her golden hair.” He first saw her walking up his neighbor’s driveway and was instantly infatuated. When explaining his fifteen year obsession, he said, “I have to be enamored. Smitten. That’s what happened when I saw Helga.” Helga, in turn was flattered. She had spent her youth in a Prussian convent, married John Testorf, a German-born naturalized American citizen and she now served as caretaker for that neighbor the elderly farmer Karl Kuerner. Clothed or unclothed, Helga accepted the challenge, an accommodating muse sitting with undying patience for countless hours, every pose becoming an unabashedly intimate conversation between artist and model. Yet as Helga insisted, if it was love, it was unconsummated love, a revelation that confirmed what Andrew once said, ‘people are going to think it’s just sexual love, but it’s not.’

The Prussian is a drybrushed watercolor that has both the toned feel of a watercolor, and the precise, dry quality of built-up layered paintings of tempera that Wyeth compared to “a cocoon-like feeling of dry lostness.” It was painted in 1974, the third year of the Wyeth/Helga collaboration, one of only nine drybrushes from the suite inclusive of 4 tempera paintings, 63 watercolors, and 164 pencil sketches that occupied the two co-conspirators for fifteen years. Her gaze is icy-blue, turned from the viewer, downward and aslant, her countenance inscrutable. If one did not know better, the effect might impress as having a surreal quality. As a realist painting, its layered process of drybrush painting weaves an impression of material textures that heightens the genuine veracity of her braided hair, classic Loden coat, and Teutonic coloration. He likely relied on three sable brushes (no. 5, no. 10, and no. 15) and not the flat brushes usually employed in applying washes to carefully work its surface. As he explained, “I work in drybrush when my emotion gets deep enough into a subject…I dip (the brush) into the watercolor color, play out the brush and bristles, squeeze out a good deal of the moisture and color with my fingers so that there is only a very small amount of paint left…A good drybrush is done over a very wet series of washes….Drybrush is layer upon layer. It’s a definite weaving process–you weave the layers of drybrush over and within the broad washes of watercolor” (John Wilmerding, Andrew Wyeth: The Helga Pictures, New York, 1987, pp. 12-13). Helga and Andrew often walked the hills surrounding Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. As she recalled, he would often point to this tree or that tree and exclaim, ‘formidable’. It is a word might best describe The Prussian and as well, its companion work, Braids, executed in 1979, the well-known tempera that portrays Helga in a new reckoning as a woman five years older. Well after all the fuss over the unveiling of the Helga paintings, Helga remained close. In a 2007 interview, when he was asked if Helga would be present at his 90th birthday party, he said, “Yeah, certainly…She’s part of the family now. I know it shocks everyone. That’s what I love about it. It shocks them.”

Wyeth’s notoriety was so great, and the discovery of the Helga images so significant, that it was the cover story on both Time and Newsweek in August of 1986. Wyeth’s depictions of Helga remain some of his most important and sought after works.

NEWSWEEK Magazine cover: Andrew Wyeth's 'Helga' | Aug. 18, 1986

MARKET INSIGHTS

- Andrew Wyeth’s artist record was set in November 2022 for $23 million with another portrait of Helga.

- This painting was shown in over 20 museums – Including the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Fine Arts Museum San Francisco, and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

- 10 of Andrew Wyeth’s top 25 drybrush sales at auction achieved over the high estimate.

- Andrew Wyeth’s market has seen a 6.9% compound annual growth rate since 1976.

Top Results at Auction

"Day Dream" (1980) sold for $23,290,000

"Ericksons" (1980) sold for $10,344,000

"Above the narrows" (1960) sold for $6,915,000

"Off Shore" (1967) sold for $6,355,000

Similar Paintings in Museum Collections

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Authentication

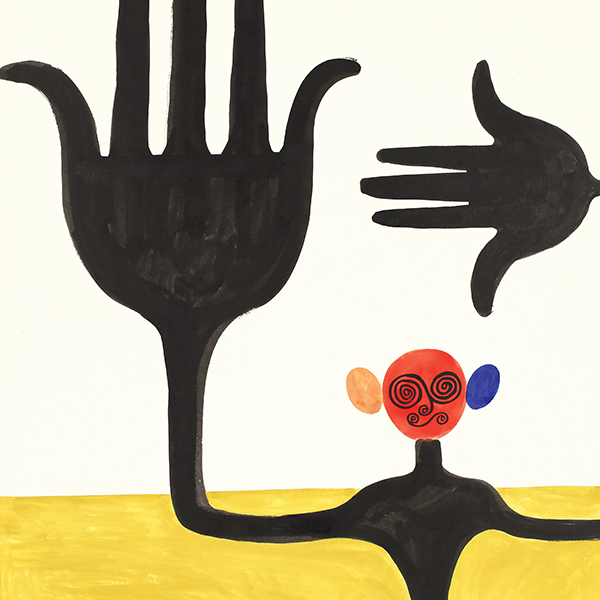

Image Gallery

Images: Copyright©PacificSunTradingCompany, Courtesy Frank E. Fowler and Warren Adelson